A regular commenter on investment and wealth management topics is Rohit Bhuta, the chief executive officer of Singapore-based Crossinvest (Asia) Pte. (See one of his previous articles here.) This article explores a number of issues around investing in non-public companies. As ever, the editors here are delighted to share such insights and invite readers to respond. Email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

“We always overestimate the change that will occur in the next two years and underestimate the change that will occur in the next ten. Don't let yourself be lulled into inaction.”

Bill Gates

It is human nature to overestimate the short-term impacts of any event or trend, and to underestimate the long-term impact. This commonly accepted behavioral trait applies to any discipline, but is particularly relevant in the financial markets we operate in today.

Witness the recent phenomenon of equity markets’ reaction to Trump’s tax policy; we are yet to see any detail, yet markets have fully priced in substantial earnings growth. In contrast, global markets almost uniformly underestimated the long-term impact of the GFC on global economic growth; economists have overestimated global growth every year since 2008.

High-conviction investing: understanding market psychology and reading long-term economic trends

At Crossinvest we are strong believers in high-conviction investing, particularly when markets are trading at such high values as they are today. Successful high-conviction equity investing requires an understanding of market psychology, investors’ propensity to overreact in the short-term, and a grasp of what drives long-term fundamental values.

Today’s markets are producing low economic returns overall, but that does not mean that value can no longer be found. There are great companies out there whose products are creating a leap forward in productivity (such as technology companies). There are companies which are well placed to take advantage of secular economic shifts (such as aged care). In a similar fashion, it is critical to understand and identify the sectors that will come under further margin pressure due to the rapidly changing digital technology landscape.

The best conviction plays aren't even listed yet

Now the above might all seem obvious to experienced investors: Of course we should be trying to spot tomorrow’s technology winners – the next Google, Uber, Fitbit, or Alibaba. But here’s the part that most investors are missing: by the time these companies list, most of the big gains have already been made.

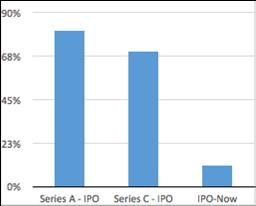

Of all of the technology stocks that have gone to IPO in the US since Google in 2004, investors prior to the initial public offering made an average of 80.8 per cent pa by the day of listing. Those that waited for the IPO averaged 11.2 per cent pa since then.

The main cause for this is the rapid development of venture capital markets globally. VC investors will now invest in companies as large as Uber. This means that the best companies do not need to list to access vast pools of capital. The average technology company is listing at an age of around 11 years, by which time the company may, in all likelihood, have reached a level of maturity – it is during these 11 years where most of the growth is likely to have occurred.

Annual returns for technology companies pre- and post-IPO

Based on listings for which information is available about their valuations at Series A (pre-revenue) or Series C (rapid growth) stages. The data is from 38 companies’ incl Google, Alibaba, Facebook, Groupon, LinkedIn, Fitbit, Square.

Equity asset class can no longer be constrained to listed only

The equity asset class is an essential component of any investment portfolio. The purpose of investing in equities as an asset class is to gain a direct, positive exposure to economic growth cycles. Many people believe that ‘equities’ means only listed market stocks bought directly, through a broker or through a managed fund.

To achieve such direct, positive exposure to economic growth cycles, and to have the flexibility to move in and out of markets, portfolio managers will allocate across several equity sub-classes and strategies: large caps, mid-caps, small caps, emerging markets, long/short or market neutral strategies. The allocations are gradually shifting now to private and unlisted companies. The emotion-driven volatility and the high valuations of listed markets have pushed many of the world’s largest and most successful investors to invest more in private capital than they do in listed equities.

Consider the Yale Endowment Fund, widely recognised as one the smartest investment teams globally. It has just 3.9 per cent of its capital in domestic (US) equities and a further 14.7 per cent in international listed equities. This however is eclipsed by 16.2 per cent in Private Equity and 16.3% in Venture Capital.

Princeton, MIT and Bowdoin College all follow Yale’s model, and have been outperforming their peers for over 20 years. Europe’s largest funds are more conservative, but on average they still have around 16 per cent in private capital vs 35 per cent in listed. Global family offices are similar, with 18 per cent in private equity and 35 per cent in listed equities.

Asset allocation of major long-term investors

.jpg)

In all three cases above, total allocation to equities is between 48 per cent and 53 per cent, but it is the mix between listed and unlisted that varies significantly. In terms of performance, the Yale Endowment has outperformed average endowments over the 5, 10, 15 and 20 year time horizons, outperformed the average family office over any period measured, and outperformed the traditional 60/40 portfolios by a massive 60% over the past 20 years (ie, a 13.1 per cent vs 8.8 per cent CAGR).

This outperformance started many years ago, long before the digital age we live in today. The rapid rise in valuations of unlisted digital companies has extended the outperformance of the leading investors that favour unlisted over listed shares. Despite this, many large financial-service organisations and large asset allocators continue to insist on old-school asset-allocation methodologies – 60 per cent investment into listed equities, with heavy trading as the backbone of value creation.

This methodology died a painful death many years ago!

The strongest reason to invest in unlisted equites

Each of the major technology-driven revolutions of the past 200 years has created, and destroyed, enormous wealth: the industrial revolution spawning machines and factories starting 1771; the age of steam and coal, iron and railways starting 1829; steel electricity and heavy engineering from 1875; and the age of oil, the automobile and mass production in 1908_.

In fact, the rise of the US as the world’s dominant economic superpower came about because it encouraged free capital and entrepreneurism right in the middle of the Industrial Revolution. Attracting entrepreneurial talent, enabling free movement of capital and investing in its manufacturing capacity led to the US overtaking Britain as the world superpower.

The digital revolution will not be any different. The implications of the digital technology “revolution” for investors are significant, particularly when coming at a time of vulnerability for traditional companies as the global economy slows and the new disruptors take over.

We did not have Uber, AirBNB, Netflix, Alibaba or Spotify ten years ago. In fact, there weren’t smartphones, smart cars, smart fridges, smart light bulbs or smart clothes, let alone microwaves that recorded discussions and take photos (☺).

We have not seen the best of this yet. The technology disruptors will change some of the world’s oldest industries over the next ten years:

-- Crop yields are expected to increase by 25 per cent using technology that combines trillions of soil observations and predicting where to plant what type and volume of crop;

-- Auto manufacturers will derive nearly half their income from selling data gathered from the connected cars that move one billion people every single day from home to work, to shops, to recreation, to a billion different places to buy a billion different things;

-- Uber itself could get disrupted when autonomous cars supplant Uber drivers and earn the owning family extra income when they aren’t being used, and by keeping cars in operation all day, further eliminating the need for an estimated 90% of expensive city carparks

And that’s before we consider the impact of virtual personal assistants, energy storage, connected home, brain-computer interface, human augmentation, 3D Bio-printing systems, smart robots, smart advisors, the sharing economy, speech to speech translation, internet of things (market size growing from $1.9tr today to $7.1tr by 2020), wearable user interfaces, consumer 3D printing, cryptocurrencies, content analytics, augmented reality, 3D scanners, or speech recognition.

Conclusion: Three top reasons for holding unlisted equities (and the one major reason not to)

There are three core reasons for including unlisted equities, particularly Venture Capital, in your portfolio:

1. Listed equity markets have become overcrowded, pushing down returns and pushing up volatility;

2. Listed and unlisted equities are actually driven by the same fundamental economic factors, so limited the universe of equities considered is detrimental;

3. Unlisted markets provide far greater access to many of the digital technology sectors

The major reason not to invest: liquidity, or more specifically the lack thereof. Unlisted shares are not for investors that need access to all of the capital all of the time. That’s why they tend to be the domain of high net worth families, pension and endowment funds.

Global economic growth overall is expected to be low, muting total equity market returns. That makes the current global environment much better suited to high conviction strategies, and as shown above, in today’s market this must include unlisted equities.

For investors the challenge is how to ensure that they have a positive economic exposure to these innovations, not just the negative impact of holding shares in the companies being disrupted.

From this dizzying array of impacts on the way we lead our lives, and therefore on the global economy, it is easy to see why humans tend to underestimate long-term impacts: the implications of big changes are well beyond the majority of people to predict. But that 5

shouldn’t mean that good advice doesn’t take into account the possibilities, because it is by understanding these possibilities that real wealth can be created.

What is next?

There is a clear need to have an investment allocation to non-listed private companies. There are, however, hundreds of VC’s, PE Companies, angel investment clubs, investment aggregators and so on – all in search for a “Holy Grail” unlisted private company.

Identifying which company, or which VC or PE firm, to invest in is complicated and will get significantly more so as the private investments’ segment matures.